CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION TO HUMAN PERFORMANCE

OVERVIEW

In its simplest form, human performance is a series of behaviors carried out to accomplish specific task objectives (results). Behavior is what people do and say—it is a means to an end. Behaviors are observable acts that can be seen and heard. In most organizations the behaviors of operators, technicians, maintenance crafts, scientists and engineers, waste handlers, and a myriad of other professionals are aggregated into cumulative acts designed to achieve mission objectives. The primary objective of the operating facilities is the continuous safe, reliable, and efficient production of mission-specific products. At the national laboratories, the primary objectives are the ongoing discovery and testing of new materials, the invention of new products, and technological advancement. The storage, handling, reconfiguration, and final repository of the legacy nuclear waste materials, as well as decontamination, decommissioning, and dismantling of old facilities and support operations used to produce America’s nuclear defense capabilities during the Cold War are other significant mission objectives. Improving human performance is a key in improving the performance of production facilities, performance of the national laboratories, and performance of cleanup and restoration.

It is not easy to anticipate exactly how trivial conditions can influence individual performance. Error-provoking aspects of facility design, procedures, processes, and human nature exist everywhere. No matter how efficiently equipment functions; how good the training, supervision, and procedures; and how well the best worker, engineer, or manager performs his or her duties, people cannot perform better than the organization supporting them. Human error is caused not only by normal human fallibility, but also by incompatible management and leadership practices and organizational weaknesses in work processes and values. Therefore, defense-in-depth with respect to the human element is needed to improve the resilience of programmatic systems and to drive down human error and events.

The aviation industry, medical industry, commercial nuclear power industry, U.S. Navy, DOE and its contractors, and other high-risk, technologically complex organizations have adopted human performance principles, concepts, and practices to consciously reduce human error and bolster controls in order to reduce accidents and events. However, performance improvement is not limited to safety. Organizations that have adopted human performance improvement (HPI) methods and practices also report improved product quality, efficiency, and productivity. HPI, as described in this course and practiced in the field, is not so much a program as it is a distinct way of thinking. This course seeks to improve understanding about human performance and to set forth recommendations on how to manage it and improve it to prevent events triggered by human error.

This course promotes a practical way of thinking about hazards and risks to human performance. It explores both the individual and leader behaviors needed to reduce error, as well as improvements needed in organizational processes and values and job-site conditions to better support worker performance. Fundamental knowledge of human and organizational behavior is emphasized so that managers, supervisors, and workers alike can better identify and eliminate error-provoking conditions that can trigger human errors leading to events in processing facilities, laboratories, D & D structures, or anywhere else. Ultimately, the attitudes and practices needed to control these situations include:

- the will to communicate problems and opportunities to improve;

- an uneasiness toward the ability to err;

- an intolerance for error traps that place people and the facility at risk;

- vigilant situational awareness;

- rigorous use of error-prevention techniques; and

- understanding the value of relationships.

INTEGRATED SAFETY MANAGEMENT AND HPI

DOE developed and began implementation of Integrated Safety Management (ISM) in 1996. Since that time, the Department has gained significant experience with its implementation. This experience has shown that the basic framework and substance of the Department’s ISM program remains valid. The experience also shows that substantial variances exist across the complex regarding familiarity with ISM, commitment to implementation, and implementation effectiveness. The experience further shows that more clarity of DOE’s role in effective ISM implementation is needed. Contractors and DOE alike have reported that clearer expectations and additional guidance on annual ISM maintenance and continuous improvement processes are needed.

Since 1996, external organizations that are also performing high-hazard work, such as commercial nuclear organizations, Navy nuclear organizations, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, and others, have also gained significant experience and insight relevant to safety management. The ISM core function of “feedback and improvement” calls for DOE to learn from available feedback and make changes to improve. This concept applies to the ISM program itself. Lessons learned from both internal and external operating experience are reflected in the ISM Manual to update the ISM program. The ISM Manual should be viewed as a natural evolution of the ISM program, using feedback for improvement of the ISM program itself. Two significant sources of external lessons learned have contributed to that Manual: (1) the research and conclusions related to high-reliability organizations (HRO) and (2) the research and conclusions related to the human performance improvement (HPI) initiatives in the commercial nuclear industry, the U.S. Navy, and other organizations. HRO and HPI tenets are very complementary with ISM and serve to extend and clarify the program’s principles and methods.

As part of the ISM revitalization effort, the Department wants to address known opportunities for improvement based on DOE experience and integrate the lessons learned from HRO organizations and HPI implementation into the Department’s existing ISM infrastructure. The Department wants to integrate the ISM core functions, ISM principles, HRO principles, HPI principles and methods, lessons learned, and internal and external best safety practices into a proactive safety culture where:

- facility operations are recognized for their excellence and high-reliability;

- everyone accepts responsibility for their own safety and the safety of others;

- organization systems and processes provide mechanisms to identify systematic weaknesses and assure adequate controls; and

- continuous learning and improvement are expected and consistently achieved.

The revitalized ISM system is expected to define and drive desired safety behaviors in order to help organizations create world-class safety performance.

In using the tools, processes, and approaches described in this HPI course, it is important to implement them within an ISM framework, not as stand-alone programs outside of the ISM framework. These tools cannot compete with ISM, but must support ISM. To the extent that these tools help to clarify and improve implementation of the ISM system, the use of these tools is strongly encouraged. The relationship between these tools and the ISM principles and functions needs to be clearly understood and articulated in ISM system descriptions if these tools impact on ISM implementation. It is also critical that the vocabulary and terminology used to apply these tools be aligned with that of ISM. Learning organizations borrow best practices whenever possible, but they must be translated into terms that are consistent and in alignment with existing frameworks.

ISM Guiding Principles

The objective of ISM is to systematically integrate safety into management and work practices at all levels so that work is accomplished while protecting the public, the workers, and the environment. This objective is achieved through effective integration of safety management into all facets of work planning and execution. In other words, the overall management of safety functions and activities becomes an integral part of mission accomplishment.

The seven guiding principles of ISMS are intended to guide organizations actions from development of safety directives to the performance of work. As reflected in the ISM Manual these principles are:

- Line Management Responsibility For Safety. Line management is directly responsible for the protection of the public, the workers, and the environment.

- Clear Roles and Responsibilities. Clear and unambiguous lines of authority and responsibility for ensuring safety shall be established and maintained at all organizational levels within the Department and its contractors.

- Competence Commensurate with Responsibilities. Personnel shall possess the experience, knowledge, skills, and abilities that are necessary to discharge their responsibilities.

- Balanced Priorities. Resources shall be effectively allocated to address safety, programmatic, and operational considerations. Protecting the public, the workers, and the environment shall be a priority whenever activities are planned and performed.

- Identification of Safety Standards and Requirements. Before work is performed, the associated hazards shall be evaluated and an agreed-upon set of safety standards and requirements shall be established which, if properly implemented, will provide adequate assurance that the public, the workers, and the environment are protected from adverse consequences.

- Hazard Controls Tailored to Work Being Performed. Administrative and engineering controls to prevent and mitigate hazards shall be tailored to the work being performed and associated hazards.

- Operations Authorization. The conditions and requirements to be satisfied for operations to be initiated and conducted shall be clearly established and agreed upon.

ISM Core Functions

Five ISM core functions provide the necessary safety management structure to support any work activity that could potentially affect the public, workers, and the environment. These functions are applied as a continuous cycle with the degree of rigor appropriate to address the type of work activity and the hazards involved.

- Define the Scope of Work. Missions are translated into work; expectations are set; tasks are identified and prioritized; and resources are allocated.

- Analyze the Hazards. Hazards associated with the work are identified, analyzed, and categorized.

- Develop and Implement Hazard Controls. Applicable standards and requirements are identified and agreed-upon; controls to prevent or mitigate hazards are identified; the safety envelope is established; and controls are implemented.

- Perform Work within Controls. Readiness to do the work is confirmed and work is carried out safely.

- Provide Feedback and Continuous Improvement. Feedback information on the adequacy of controls is gathered; opportunities for improving how work is defined and planned are identified and implemented; line and independent oversight is conducted; and, if necessary, regulatory enforcement actions occur.

Human error can have a negative affect at each stage of the ISM work cycle; for example:.

- Define Work Scope: Errors in defining work can lead to mistakes in analyzing hazards.

- Analyze Hazards: Without the correct hazards identified, errors will be made in identifying adequate controls.

- Develop Controls: Without an effective set of controls, minor work errors can lead to significant events.

- Perform Work: If the response to the event only focuses on the minor work error, the other contributing errors will not be addressed.

Integration of ISM and HPI

Work planning and control processes derived from ISM are key opportunities for enhancement by application of HPI concepts and tools. In fact, an almost natural integration can occur when the HPI objectives—reducing error and strengthening controls – are used as integral to implementing the ISM core functions. Likewise the analytical work that goes into reducing human error and strengthening controls supports the ISM core functions.

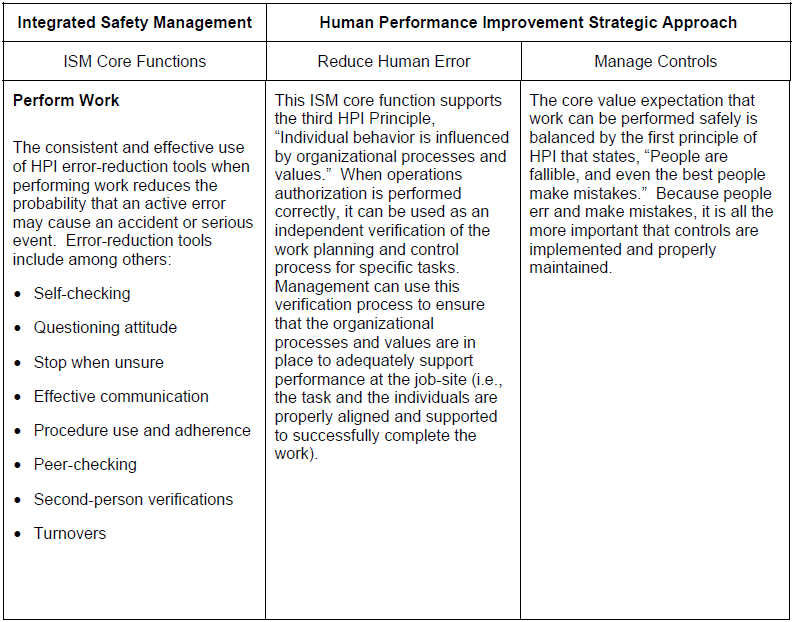

For purposes of this course, a few examples of this integration are illustrated in the following table. The ISM core functions are listed in the left column going down the table. The HPI objectives appear as headers in the second and third column on the table.

Integration of ISM and HPI

As illustrated in the table above, the integration of HPI methods and techniques to reduce error and manage controls supports the ISMS core functions.

The following leadership behaviors support ISMS Guiding Principle 1—line management responsibility for safety.

- Facilitate open communication.

- Promote teamwork.

- Reinforce desired behaviors.

- Eliminate latent organizational weaknesses.

- Value prevention of errors.

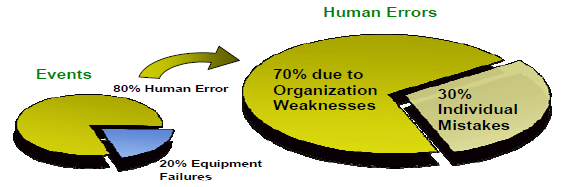

Perspective on Human Performance and Events

The graphic below illustrates what is known about the role of human performance in causing events. About 80 percent of all events are attributed to human error. In some industries, this number is closer to 90 percent. Roughly 20 percent of events involve equipment failures. When the 80 percent human error is broken down further, it reveals that the majority of errors associated with events stem from latent organizational weaknesses (perpetrated by humans in the past that lie dormant in the system), whereas about 30 percent are caused by the individual worker touching the equipment and systems in the facility. Clearly, focusing efforts on reducing human error will reduce the likelihood of events.

An analysis of significant events in the commercial nuclear power industry between 1995 and 1999 indicated that three of every four events were attributed to human error, as reported by INPO. Additionally, a Nuclear Regulatory Commission review of events in which fuel was damaged while in the reactor showed that human error was a common factor in 21 of 26 (81 percent) events. The report disclosed that “the risk is in the people—the way they are trained, their level of professionalism and performance, and the way they are managed.” Human error leading to adverse consequences can be very costly: it jeopardizes an organization’s ability to protect its workforce, its physical facility, the public, and the environment from calamity. Human error also affects the economic bottom line. Very few organizations can sustain the costs associated with a major accident (such as, product, material and facility damage, tool and equipment damage, legal costs, emergency supplies, clearing the site, production delays, overtime work, investigation time, supervisors’ time diverted, cost of panels of inquiry). It should be noted that costs to operations are also incurred from errors by those performing security, work control, cost and schedule, procurement, quality assurance, and other essential but non-safety-related tasks. Human performance remains a significant factor for management attention, not only from a safety perspective, but also from a financial one.

A traditional belief is that human performance is a worker-focused phenomenon. This belief promotes the notion that failures are introduced to the system only through the inherent unreliability of people—Once we can rid ourselves of a few bad performers, everything will be fine. There is nothing wrong with the system. However, experience indicates that weaknesses in organizational processes and cultural values are involved in the majority of facility events. Accidents result from a combination of factors, many of which are beyond the control of the worker. Therefore, the organizational context of human performance is an important consideration. Event-free performance requires an integrated view of human performance from those who attempt to achieve it; that is, how well management, staff, supervision, and workers function as a team and the degree of alignment of processes and values in achieving the facility’s economic and safety missions.

Human Performance for Engineers and Knowledge Workers

Engineers and other knowledge-based workers contribute differently than first-line workers to facility events. A recent study completed for the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) by the Idaho National Engineering and Environmental Laboratory (INEEL) indicates that human error continues to be a causal factor in 79 percent of industry licensee events. Within those events, there were four latent failures (undetected conditions that did not achieve the desired end(s) for every active failure. More significantly, design and design change problems were a factor in 81 percent of the events involving human error. Recognizing that engineers and other knowledge-based workers make different errors, INPO developed a set of tools specific to their needs.

With engineers, specifically, the errors made can become significant if not caught early. As noted in research conducted at one DOE site, because engineers as a group are highly educated, narrowly focused, and have personalities that tend to be introverted and task-oriented, they tend to be critical of others, but not self-critical.10 If they are not self-critical, their errors may go undetected for long periods of time, sometimes years. This means that it is unlikely that the engineer who made the mistake would ever know that one had been made, and the opportunity for learning is diminished. Thus, human performance techniques aimed at this group of workers need to be more focused on the errors they make while in the knowledge-based performance mode as described in Chapter 2.

The Work Place

The work place or job site is any location where either the physical plant or the “paper” plant (the aggregate of all the documentation that helps control the configuration of the physical plant) can be changed. The systems, structures, and components used in the production processes make up the physical plant. Error can come from either the industrial plant or the paper plant. All human activity involves the risk of error. Flaws in the paper plant can lie dormant and can lead to undesirable outcomes in the physical plant or even personal injury. Front-line workers “touch” the physical plant as they perform their assigned tasks. Supervisors observe, direct, and coach workers. Engineers and other technical staff perform activities that alter the paper plant or modify processes and procedures that direct the activities of workers in the physical plant. Managers influence worker and staff behavior by their oral or written directives and personal example. The activities of all these individuals need to be controlled.

Individuals, Leaders, and Organizations

This course describes how individuals, leaders, and the organization as a whole influence human performance. The role of the individual in human performance is discussed in Chapter 2, “Reducing Error.” The role of the organization is discussed in Chapter 3, “Managing Controls.” The role of the leader, as well as the leader’s responsibilities for excellence in human performance, is discussed in Chapter 4, “Culture and Leadership”. The following provides a general description of each of theses entities:

- Individual — An employee in any position in the organization from yesterday’s new hire in the storeroom to the senior vice president in the corner office.

- Leader — Any individual who takes personal responsibility for his or her performance and the facility’s performance and attempts to positively influence the processes and values of the organization. Managers and supervisors are in positions of responsibility and as such are organizational leaders. Some individuals in these positions, however, may not exhibit leadership behaviors that support this definition of a leader. Workers, although not in managerial positions of responsibility, can be and are very influential leaders. The designation as a leader is earned from subordinates, peers, and superiors.

- Organization — A group of people with a shared mission, resources, and plans to direct people’s behavior toward safe and reliable operation. Organizations direct people’s behavior in a predictable way, usually through processes and its value and belief systems. Workers, supervisors, support staff, managers, and executives all make up the organization.

HUMAN PERFORMANCE

What is human performance? Because most people cannot effectively manage what they do not understand, this question is a good place to start. Understanding the answer helps explain why improvement efforts focus not only on results, but also on behavior. Good results can be achieved with questionable behavior. In contrast, bad results can be produced despite compliant behavior, as in the case of following procedures written incorrectly. Very simply, human performance is behavior plus results (P = B + R).

Behavior

Behavior is what people do and say—a means to an end. Behavior is an observable act that can be seen and heard, and it can be measured. Consistent behavior is necessary for consistent results. For example, a youth baseball coach cannot just shout at a 10-year old pitcher from the dugout to “throw strikes.” The child may not know how and will become frustrated. To be effective, the coach must teach specific techniques—behaviors—that will help the child throw strikes more consistently. This is followed up with effective coaching and positive reinforcement. Sometimes people will make errors despite their best efforts. Therefore, behavior and its causes are extremely valuable as the signal for improvement efforts to anticipate, prevent, catch, or recover from errors. For long-term, sustained good results, a close observation must be conducted of what influences behavior, what motivates it, what provokes it, what shapes it, what inhibits it, and what directs it, especially when handling facility equipment.

Results

Performance infers measurable results. Results, good or bad, are the outcomes of behavior encompassing the mental processes and physical efforts to perform a task. Within an organization, the “end” is that set of outcomes manifested by people’s health and well-being; the environment; the safe, reliable, and efficient production of defense products; the discovery of new scientific knowledge; the invention and testing of new products; and the disposition of legacy wastes and facilities. Events usually involve such things as challenges to reactor safety (where applicable), industrial/radiological safety, environmental safety, quality, reliability, and productivity. Event-free performance is the desired result, but is dependent on reducing error, both where people touch the facility and where they touch the paper (procedures, instructions, drawings, specifications, and the like). Event-free performance is also dependent on ensuring the integrity of controls, controls, barriers, and safeguards against the residual errors that still occur.

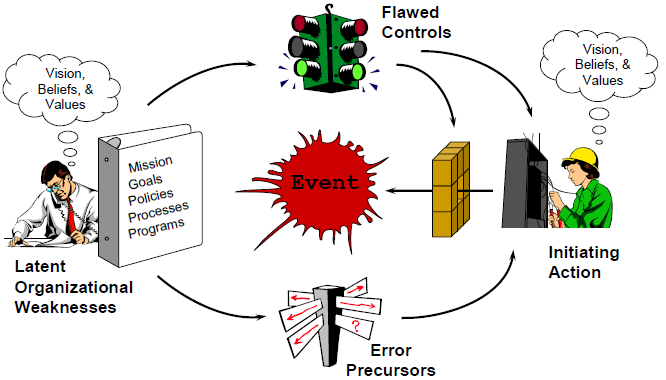

ANATOMY OF AN EVENT

Typically, events are triggered by human action. In most cases, the human action causing the event was in error. However, the action could have been directed by a procedure; or it could have resulted from a violation—a shortcut to get the job done. In any case, an act initiates the undesired consequences. The graphic below provides an illustration of the elements that exist before a typical event occurs. Breaking the linkages may prevent events.

Event

An event, as defined earlier, is an unwanted, undesirable change in the state of facility structures, systems, or components or human/organizational conditions (health, behavior, administrative controls, environment, etc.) that exceeds established significance criteria. Events involve serious degradation or termination of the equipment’s ability to perform its required function. Other definitions include: an outcome that must be undone; any facility condition that does not achieve its goals; any undesirable consequence; and a difference between what is and what ought to be.

Initiating Action

The initiating action is an action by an individual, either correct, in error, or in violation, that results in a facility event. An error is an action that unintentionally departs from an expected behavior. A violation is a deliberate, intentional act to evade a known policy or procedure requirement and that deviates from sanctioned organizational practices. Active errors are those errors that have immediate, observable, undesirable outcomes and can be either acts of commission or omission. The majority of initiating actions are active errors. Therefore, a strategic approach to preventing events should include the anticipation and prevention of active errors.

Flawed Controls

Flawed controls are defects that, under the right circumstances, may inhibit the ability of defensive measures to protect facility equipment or people against hazards or fail to prevent the occurrence of active errors. Controls or barriers are methods that:

- protect against various hazards (such as radiation, chemical, heat);

- mitigate the consequences of the hazard (for example, reduced operating safety margin, personal injury, equipment damage, environmental contamination, cost); and

- promote consistent behavior.

When an event occurs, there is either a flaw with existing controls or appropriate controls are not in place.

Error Precursors

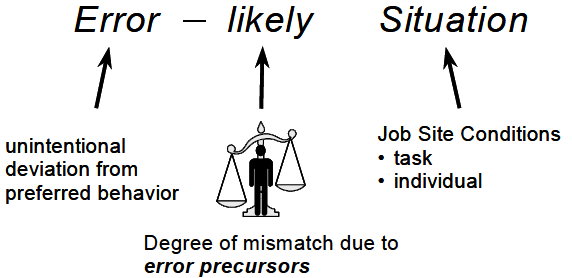

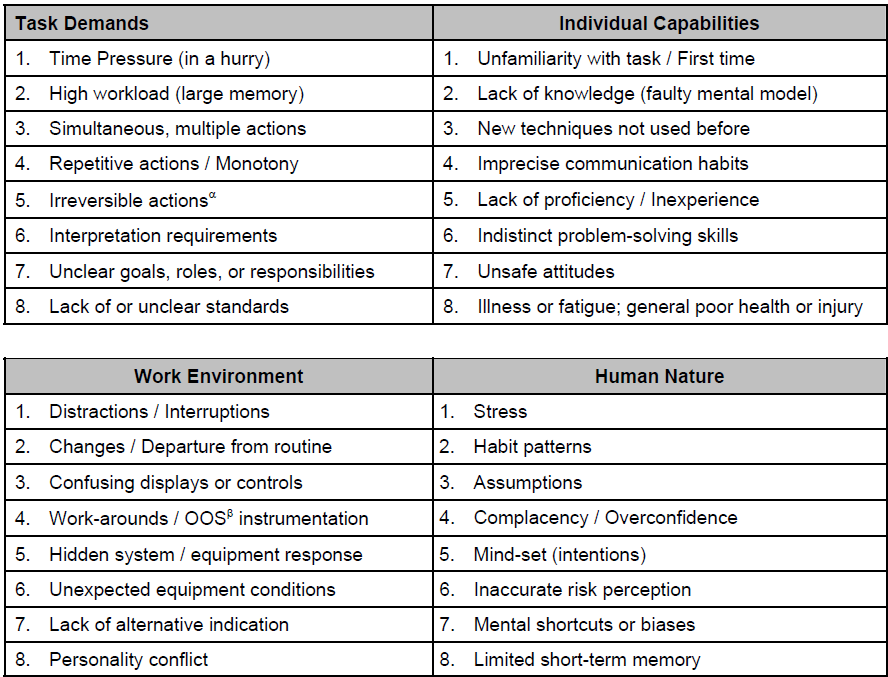

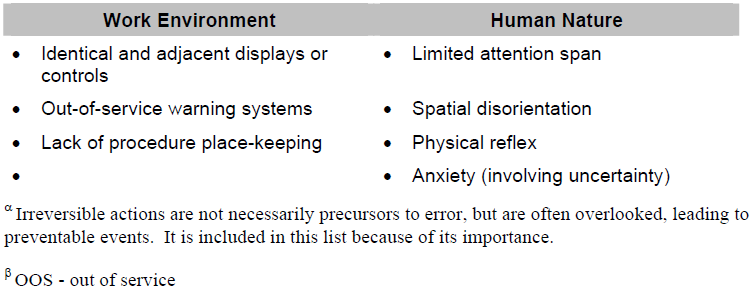

Error precursors are unfavorable prior conditions at the job site that increase the probability for error during a specific action; that is, error-likely situations. An error-likely situation—an error about to happen—typically exists when the demands of the task exceed the capabilities of the individual or when work conditions aggravate the limitations of human nature. Error-likely situations are also known as error traps.

Latent Organizational Weaknesses

Latent organizational weaknesses are hidden deficiencies in management control processes (for example, strategy, policies, work control, training, and resource allocation) or values (shared beliefs, attitudes, norms, and assumptions) that create work place conditions that can provoke errors (precursors) and degrade the integrity of controls (flawed controls). Latent organizational weaknesses include system-level weaknesses that may exist in procedure development and review, engineering design and approval, procurement and product receipt inspection, training and qualification system(s), and so on. The decisions and activities of managers and supervisors determine what is done, how well it is done, and when it is done, either contributing to the health of the system(s) or further weakening its resistance to error and events. System-level weaknesses are aggregately referred to as latent organizational weaknesses. Consequently, managers and supervisors should perform their duties with the same uneasy respect for error-prone work environments as workers. A second strategic thrust to preventing events should be the identification and elimination of latent organizational weaknesses.

STRATEGIC APPROACH FOR HUMAN PERFORMANCE

The strategic approach to improving human performance within an organization’s community embraces two primary challenges:

- Anticipate, prevent, catch, and recover from active errors at the job site.

- Identify and eliminate latent organizational weaknesses that provoke human error and degrade controls against error and the consequences of error.

If opportunities to err are not methodically identified, preventable errors will not be eliminated. Even if opportunities to err are systematically identified and prevented, people may still err in unanticipated and creative ways. Consequently, additional means are necessary to protect against errors that are not prevented or anticipated. Reducing the error rate minimizes the frequency, but not the severity of events. Only controls can be effective at reducing the severity of the outcome of error. Defense-in-depth—controls, or safeguards arranged in a layered fashion—provides assurance such that if one fails, remaining controls will function as needed to reduce the impact on the physical facility.

To improve human performance and facility performance, efforts should be made to (1) reduce the occurrence of errors at all levels of the organization and (2) enhance the integrity of controls, or safeguards discovered to be weak or missing. Reducing errors (Re) and managing controls (Mc) will lead to zero significant events (ØE). The formula for achieving this goal is Re + Mc → ØE. Eliminating significant facility events will result in performance improvement within the organization.

Reducing Error

An effective error-reduction strategy focuses on work execution because these occasions present workers with opportunities to harm key assets, reduce productivity, and adversely affect quality through human error. Work execution involves workers having direct contact with the facility, when they touch equipment and when knowledge workers touch the paper that influences the facility (procedures, instructions, drawings, specifications, etc.). During work execution, the human performance objective is to anticipate, prevent, or catch active errors, especially at critical steps, where error-free performance is absolutely necessary. While various work planning taxonomies may be used, opportunities for reducing error are particularly prevalent in what is herein expressed as preparation, performing and feedback.

- Preparation — planning – identifying the scope of work, associated hazards, and what is to be avoided, including critical steps; job-site reviews and walkdowns – identifying potential job-site challenges to error-free performance; task assignment – putting the right people on the job in light of the job’s task demands; and task previews and pre-job briefings – identifying the scope of work including critical steps, associated hazards, and what has to be avoided by anticipating possible active errors and their consequences.

- Performance — performing work with a sense of uneasiness; maintaining situational awareness; rigorous use of human performance tools for important human actions, avoiding unsafe or at-risk work practices; supported with quality supervision and teamwork.

- Feedback — reporting – conveying information on the quality of work preparation, related resources, and work place conditions to supervision and management; behavior observations – workers receiving coaching and reinforcement on their performance in the field through observations by managers and supervisors.

Chapter 2 focuses more on anticipating, preventing, and catching human error at the job-site.

Managing Controls

Events involve breaches in controls or safeguards. As mentioned earlier, errors still occur even when opportunities to err are systematically identified and eliminated. It is essential therefore that management take an aggressive approach to ensure controls function as intended. The top priority to ensure safety from human error is to identify, assess, and eliminate hazards in the workplace. These hazards are most often closely related to vulnerabilities with controls. They have to be found and corrected. The most important aspect of this strategy is an assertive and ongoing verification and validation of the health of controls. Ongoing self-assessments are employed to scrutinize controls, and then the vulnerabilities are mended using the corrective action program. A number of taxonomies of safety controls have been developed. For purposes of this discussion of the HPI strategic approach, four general types of controls are reviewed in brief.

- Control of Hazards by elimination or substitution – Organizations evaluate operations, procedures and facilities to identify workplace hazards. Management implements a hazard prevention and elimination process. When hazards are identified in the workplace they are prioritized and actions are taken based on risks to the workers. Management puts in place protective measures until such time as the hazard(s) can be eliminated. An assessment of the hazard control(s) is carried out to verify that the actions taken to eliminate the hazard are effective and enduring.

- Engineered features— These provide the facility with the physical ability to protect from errors. To optimize this set of controls , equipment is reliable and is kept in a configuration that is resistant to simple human error and allows systems and components to perform their intended functions when required. Facilities with high equipment reliability, effective configuration control, and minimum human-machine vulnerabilities tend to experience fewer and less severe facility events than those that struggle with these issues. How carefully facility equipment is designed, operated, and maintained (using human-centered approaches) affects the level of integrity of this line of protection.

- Administrative provisions— Policies, procedures, training, work practices processes, administrative controls and expectations direct people’s activities so that they are predictable and safe and limit their exposure to hazards, especially for work performed in and on the facility. All together such controls help people anticipate and prepare for problems. Written instructions specify what, when, where, and how work is to be done and what personal protective equipment workers are to use. The rigor with which people follow and perform work activities according to correctly written procedures, expectations, and standards directly affects the integrity of this line of protection.

- Cultural norms — These are the assumptions, values, beliefs, and attitudes and the related leadership practices that encourage either high standards of performance or mediocrity, open or closed communication, or high or low standards of performance. Personnel in highly reliable organizations practice error-prevention rigorously, regardless of their perception of a task’s risk and simplicity, how routine it is, and how competent the performer. The integrity of this line of defense depends on people’s appreciation of the human’s role in safety, the respect they have for each other, and their pride in the organization and the facility.

- Oversight — Accountability for personnel and facility safety, for security, and for ethical behavior in all facets of facility operations, maintenance, and support activities is achieved by a kind of “social contract” entered into willingly by workers and management where a “just culture” prevails. In a just culture, people who make honest errors and mistakes are not blamed while those who willfully violate standards and expectations are censured. Workers willingly accept responsibility for the consequences of their actions, including the rewards or sanctions (see “accountability” in the glossary). They feel empowered to report errors and near misses. This accountability helps verify margins, the integrity of controls and processes, as well as the quality of performance. Performance improvement activities facilitate the accountability of line managers through structured and ongoing assessments of human performance, trending, field observations, and use of the corrective action program, among others. The integrity of this line of defense depends on management’s commitment to high levels of human performance and consistent follow-through to correct problems and vulnerabilities.

Chapter 3 focuses on controls and their management. Chapter 4 emphasizes the role managers and informal leaders play in shaping safety culture.

PRINCIPLES OF HUMAN PERFORMANCE

Five simple statements, listed below, are referred to as the principles or underlying truths of human performance. Excellence in human performance can only be realized when individuals at all levels of the organization accept these principles and embrace concepts and practices that support them. These principles are the foundation blocks for the behaviors described and promoted in this course. Integrating these principles into management and leadership practices, worker practices, and the organization’s processes and values will be instrumental in developing a working philosophy and implementing strategies for improving human performance within your organization.

- People are fallible, and even the best people make mistakes.

Error is universal. No one is immune regardless of age, experience, or educational level. The saying, “to err is human,” is indeed a truism. It is human nature to be imprecise—to err. Consequently, error will happen. No amount of counseling, training, or motivation can alter a person’s fallibility. Dr. James Reason, author of Human Error (1990) wrote: It is crucial that personnel and particularly their managers become more aware of the human potential for errors, the task, workplace, and organizational factors that shape their likelihood and their consequences. Understanding how and why unsafe acts occur is the essential first step in effective error management. - Error-likely situations are predictable, manageable, and preventable.

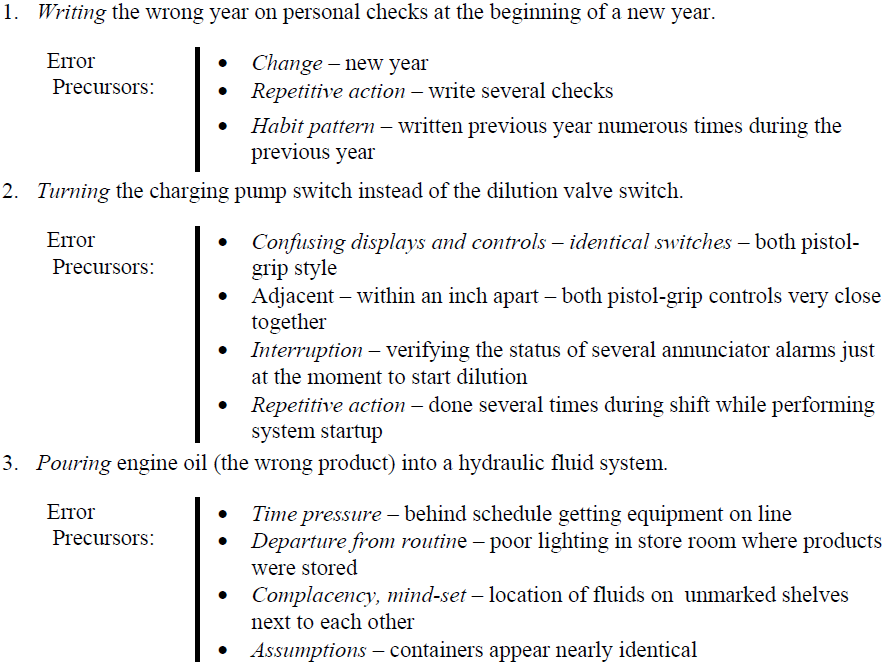

Despite the inevitability of human error in general, specific errors are preventable. Just as we can predict that a person writing a personal check at the beginning of a new year stands a good chance of writing the previous year on the check, a similar prediction can be made within the context of work at the job site. Recognizing error traps and actively communicating these hazards to others proactively manages situations and prevents the occurrence of error. By changing the work situation to prevent, remove, or minimize the presence of conditions that provoke error, task and individual factors at the job site can be managed to prevent, or at least minimize, the chance for error. - Individual behavior is influenced by organizational processes and values. Organizations are goal-directed and, as such, their processes and values are developed to direct the behavior of the individuals in the organization. The organization mirrors the sum of the ways work is divided into distinct jobs and then coordinated to conduct work and generate deliverables safely and reliably. Management is in the business of directing workers’ behaviors. Historically, management of human performance has focused on the “individual error-prone or apathetic workers.” Work is achieved, however, within the context of the organizational processes, culture, and management planning and control systems. It is exactly these phenomena that contribute most of the causes of human performance problems and resulting facility events.

- People achieve high levels of performance because of the encouragement and reinforcement received from leaders, peers, and subordinates.

The organization is perfectly tuned to get the performance it receives from the workforce. All human behavior, good and bad, is reinforced, whether by immediate consequences or by past experience. A behavior is reinforced by the consequences that an individual experiences when the behavior occurs. The level of safety and reliability of a facility is directly dependent on the behavior of people. Further, human performance is a function of behavior. Because behavior is influenced by the consequences workers experience, what happens to workers when they exhibit certain behaviors is an important factor in improving human performance. Positive and immediate reinforcement for expected behaviors is ideal. - Events can be avoided through an understanding of the reasons mistakes occur and application of the lessons learned from past events (or errors).

Traditionally, improvement in human performance has resulted from corrective actions derived from an analysis of facility events and problem reports—a method that reacts to what happened in the past. Learning from our mistakes and the mistakes of others is reactive—after the fact—but important for continuous improvement. Human performance improvement today requires a combination of both proactive and reactive approaches. Anticipating how an event or error can be prevented is proactive and is a more cost-effective means of preventing events and problems from developing.

Chapter 2: REDUCING ERROR

INTRODUCTION

As capable and ingenious as humans are, we do err and make mistakes. It is precisely this part of human nature that we want to explore in the first part of this chapter. This inquiry includes discussions of human characteristics, unsafe attitudes, and at-risk behaviors that make people vulnerable to errors. A better understanding of what is behind the first principle of human performance, “people are fallible, even the best make mistakes,” will help us better compensate for human error through more rigorous use of error-reduction tools and by improving controls. Certain sections of this chapter are considered essential reading and will be flagged as such at the beginning of the section.

HUMAN FALLIBILITY (Essential Reading)

Human nature encompasses all the physical, biological, social, mental, and emotional characteristics that define human tendencies, abilities, and limitations. One of the innate characteristics of human nature is imprecision. Unlike a machine that is precise—each time, every time—people are imprecise, especially in certain situations. For instance, humans tend to perform poorly under high stress and time pressure. Because of “fallibility,” human beings are vulnerable to external conditions that cause them to exceed the limitations of human nature. Vulnerability to such conditions makes people susceptible to error. Susceptibility to error is augmented when people work within complex systems (hardware or administrative) that have concealed weaknesses—latent conditions that either provoke error or weaken controls against the consequences of error.

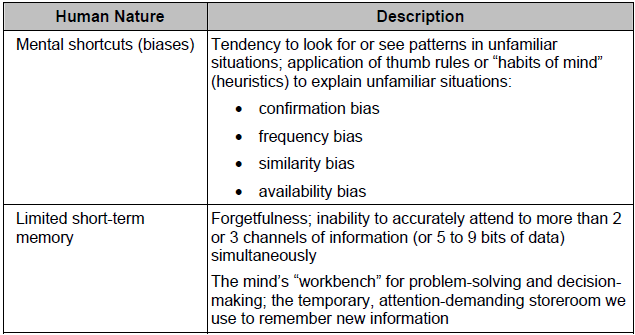

Common Traps of Human Nature

People tend to overestimate their ability to maintain control when they are doing work. Maintaining control means that everything happens that is supposed to happen during performance of a task and nothing else. There are two reasons for this overestimation of ability. First, consequential error is rare. Most of the time when errors occur, little or nothing happens. So, people reason that errors will be caught or won’t be consequential. Second, there is a general lack of appreciation of the limits of human capabilities. For instance, many people have learned to function on insufficient rest or to work in the presence of enormous distractions or wretched environmental conditions (extreme heat, cold, noise, vibration, and so on). These conditions become normalized and accepted by the individual. But, when the limits of human capabilities are exceeded (fatigue or loss of situational awareness, for example), the likelihood of error increases. The common characteristics of human nature addressed below are especially accentuated when work is performed in a complex work environment.

Stress. Stress in itself is not a bad thing. Some stress is normal and healthy. Stress may result in more focused attention, which in some situations could actually be beneficial to performance. The problem with stress is that it can accumulate and overpower a person, thus becoming detrimental to performance. Stress can be seen as the body’s mental and physical response to a perceived threat(s) in the environment. The important word is perceived; the perception one has about his or her ability to cope with the threat. Stress increases as familiarity with a situation decreases. It can result in panic, inhibiting the ability to effectively sense, perceive, recall, think, or act. Anxiety and fear usually follow when an individual feels unable to respond successfully. Along with anxiety and fear, memory lapses are among the first symptoms to appear. The inability to think critically or to perform physical acts with accuracy soon follows.

Avoidance of Mental Strain. Humans are reluctant to engage in lengthy concentrated thinking, as it requires high levels of attention for extended periods. Thinking is a slow, laborious process that requires great effort. Consequently, people tend to look for familiar patterns and apply well-tried solutions to a problem. There is the temptation to settle for satisfactory solutions rather than continue seeking a better solution. The mental biases, or shortcuts, often used to reduce mental effort and expedite decision-making include:

- Assumptions – A condition taken for granted or accepted as true without verification of the facts.

- Habit – An unconscious pattern of behavior acquired through frequent repetition.

- Confirmation bias – The reluctance to abandon a current solution—to change one’s mind—in light of conflicting information due to the investment of time and effort in the current solution. This bias orients the mind to “see” evidence that supports the original supposition and to ignore or rationalize away conflicting data.

- Similarity bias – The tendency to recall solutions from situations that appear similar to those that have proved useful from past experience.

- Frequency bias – A gamble that a frequently used solution will work; giving greater weight to information that occurs more frequently or is more recent.

- Availability bias – The tendency to settle on solutions or courses of action that readily come to mind and appear satisfactory; more weight is placed on information that is available (even though it could be wrong). This is related to a tendency to assign a cause-effect relationship between two events because they occur almost at the same time.

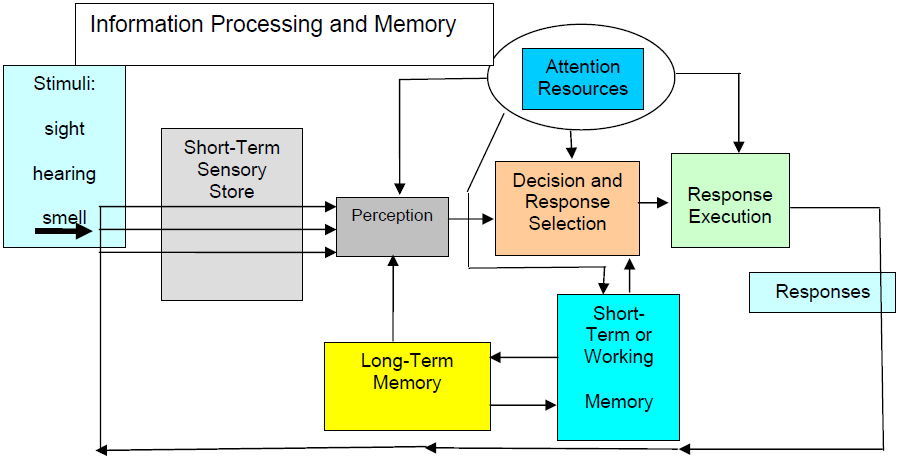

Limited Working Memory. The mind’s short-term memory is the “workbench” for problem-solving and decision-making. This temporary, attention-demanding storeroom is used to remember new information and is actively involved during learning, storing, and recalling information. Most people can reliably remember a limited number of items at a time often expressed as 7+1 or -2. The limitations of short-term memory are at the root of forgetfulness; forgetfulness leads to omissions when performing tasks. Applying place-keeping techniques while using complex procedures compensates for this human limitation.

Limited Attention Resources. The limited ability to concentrate on two or more activities challenges the ability to process information needed to solve problems. Studies have shown that the mind can concentrate on, at most, two or three things simultaneously. Attention is a limited commodity—if it is strongly drawn to one particular thing it is necessarily withdrawn from other competing concerns. Humans can only attend to a very small proportion of the available sensory data. Also, preoccupation with some demanding sensory input or distraction by some current thoughts or worries can capture attention. Attention focus (concentration) is hard to sustain for extended periods of time. The ability to concentrate depends very much upon the intrinsic interest of the current object of attention. Self-checking (Stop, Think, Act, Review) is an effective tool for helping individuals maintain attention.

Mind-Set. People tend to focus more on what they want to accomplish (a goal) and less on what needs to be avoided because human beings are primarily goal-oriented by nature. As such, people tend to “see” only what the mind expects, or wants, to see. The human mind seeks order, and, once established, it ignores anything outside that mental model. Information that does not fit a mind-set may not be noticed; hence people tend to miss conditions and circumstances which are not expected. Likewise because they expect certain conditions and circumstances, they tend to see things that are not really present. A focus on goal tends to conceal hazards, leading to inaccurate perception of risks. Errors, hazards, and consequences usually result from either incomplete information or assumptions. Pre-job briefings, if done mindfully, help people recognize what needs to be avoided as well as what needs to be accomplished.

Difficulty Seeing One’s Own Error. Individuals, especially when working alone, are particularly susceptible to missing errors. People who are too close to a task, or are preoccupied with other things, may fail to detect abnormalities. People are encouraged to “focus on the task at hand.” However, this is a two-edged sword. Because of our tendency for mind-set and our limited perspective, something may be missed. Peer-checking, as well as concurrent and independent verification techniques, help detect errors that an individual can miss. Engineers and some knowledge workers, by the nature of their focus on producing detailed information, can be especially susceptible to not being appropriately self-critical.

Limited Perspective. Humans cannot see all there is to see. The inability of the human mind to perceive all facts pertinent to a decision challenges problem-solving. This is similar to attempting to see all the objects in a locked room through the door’s keyhole. It is technically known as “bounded rationality.” Only parts of a problem receive one’s attention while other parts remain hidden to the individual. This limitation causes an inaccurate mental picture, or model, of a problem and leads to underestimating the risk. A well-practiced problem-solving methodology is a key element to effective operating team performance during a facility abnormality and also for the management team during meetings to address the problems of operating and maintaining the facility.

Susceptibility To Emotional/Social Factors. Anger and embarrassment adversely influence team and individual performance. Problem-solving ability especially in a group may be weakened by these and other emotional obstacles. Pride, embarrassment, and the group may inhibit critical evaluation of proposed solutions, possibly resulting in team errors.

Fatigue. People get tired. In general, Americans are working longer hours now than a generation ago and are sleeping less. Physical, emotional, and mental fatigue can lead to error and poor judgment. Fatigue is affected by both on-the-job demands (production pressures, environment, and reduced staffing) and off-duty life style (diet and sleep habits). Fatigue leads to impaired reasoning and decision-making, impaired vigilance and attention, slowed mental functioning and reaction time, loss of situational awareness, and adoption of shortcuts. Acquiring adequate rest is an important factor in reducing individual error rate.

Presenteeism. Some employees will be present in the need to belong to the workplace despite a diminished capacity to perform their jobs due to illness or injury. The tendency of people to continue working with minor health problems can be exacerbated by lack of sick leave, a backlog of work, or poor access to medical care, and can lead to employees working with significant impairments. Extreme cases can include individuals who fail to seek care for chronic and disabling physical and mental health problems in order to keep working.

Unsafe Attitudes and At-Risk Behaviors

An attitude is a state of mind, or feeling, toward an object or subject. Attitudes are influenced by many factors. They are formulated by one’s experiences, by examples and guidance from others, through acquired beliefs and the like. Attitudes can develop as a result of educational experiences, and, in such cases, it can be said that attitudes may be chosen.14 Attitudes can also be acculturated—formulated by one’s experiences and influences from beliefs and behaviors within one’s peer group. For example, the Mohawk Indians, often referred to as “skywalkers,” are renowned for their extraordinary ability to walk high steel beams with balance and grace, seemingly without any fear. It is commonly thought that this absence of fear of height was inborn among the woodland Indians. It seems more likely that the trait was learned.

Anyone can possess an unsafe attitude. Unsafe attitudes are derived from beliefs and assumptions about workplace hazards. Hazards are threats of harm. Harm includes physical damage to equipment, personal injury, and even simple human error. Unsafe attitudes blind people to the precursors to harm (exposure to danger). Notice that hazards are not confined to the industrial facility; they exist in the office facility as well. The unsafe attitudes that are described below are detrimental to excellent human performance and to the physical facility and are usually driven by one’s perception of risk.

People in general are poor judges of risk and commonly underestimate it.

Examples of Risk Behaviors

- Before the Park Service made it unlawful to feed the bears at Yellowstone National Park, in the summer time a long line of automobiles would be stopped at the side the road where the bears foraged for food in garbage cans. Tourists eagerly fed the animals through open windows—a very risky business. Every day of the year in our larger cities, television news cameras chronicle tragedies that have resulted from someone taking undue risks: trying to beat the train at a railroad crossing; playing with a loaded firearm; swimming in dangerous waters; binge drinking following the “big game”; and the like.

Each individual “decides” what to be afraid of and how afraid he or she should be. People often think of risk in terms of probability, or likelihood, without adequately considering the possible consequences or severity of the outcome. For instance, a mountain climber presumes he will not slip or fall because most people don’t slip and fall when they climb. The climber gives little thought to the consequences of a fall should one occur. (broken bones, immobility, unconsciousness, no quick emergency response) People take the following factors into consideration in varying degrees in assessing the risk of a situation.16 People are less afraid of risks or situations:

- that they feel they have “control” over;

- that provide some benefit(s) they want;

- the more they know about and ”live” with the hazard

- that they choose to take rather than those imposed on them;

- that are “routine” in contrast to those that are new or novel;

- that come from people, places, or organizations they trust;

- when they are unaware of the hazard(s);

- that are natural versus those that are man-made; and

- that affect others.

It has been said that risk perception tends to be guided more by our heart than our head. What feels safe may, in fact, be dangerous. The following unsafe attitudes create danger in the work place. Awareness of these unsafe, detrimental attitudes among the workforce is a first step toward applying error-prevention methods.

- Pride. An excessively high opinion of one’s ability; arrogance. Being self-focused, pride tends to blind us to the value of what others can provide, hindering teamwork. People with foolish pride think their competence is being called into question when they are corrected about not adhering to expectations. The issue is human fallibility, not their competence. This attitude is evident when someone responds, “Don’t tell me what to do!” As commander of the U.N. forces in Korea in 1950, General Douglas MacArthur (contrary to the President’s strategy) sought to broaden the war against North Korea and China. President Truman and the Joint Chiefs were fearful that MacArthur’s strategy, in opposition to the administration’s “limited” war, could bring the Soviet Union into the war and lead to a possible third world war. In April 1951, Truman fired MacArthur for insubordination. At the Senate Foreign Relations and Armed Services committee hearing on MacArthur’s dismissal, the General would admit to no mistakes, no errors of judgment, and belittled the danger of a larger conflict.

- Heroic. An exaggerated sense of courage and boldness, like that of General George Armstrong Custer. At Little Big Horn, he was so impetuous and eager for another victory that he ignored advice from his scouts and fellow officers and failed to wait for reinforcements that were forthcoming. He rode straight into battle against an overwhelming force—the Sioux and Cheyenne braves—and to his death with over 200 of his men. Heroic reactions are usually impulsive. The thinking is that something has to be done fast or all is lost. This perspective is characterized by an extreme focus on the goal without consideration of the hazards to avoid.

- Fatalistic. A defeatist belief that all events are predetermined and inevitable and that nothing can be done to avert fate: “que será, será” (what will be will be) or “let the chips fall as they may.” The long drawn-out trench warfare that held millions of men on the battlefields of northern France in World War I caused excessive fatalistic responses among the ranks of soldiers on both sides of the fighting. “Week after week, month after month, year after year, the same failed offensive strategy prevailed. Attacking infantry forces always faced a protected enemy and devastating machine gun fire. Millions of men killed and wounded, yet the Generals persisted. The cycle continued—over the top, early success, then overwhelming losses and retreat.”

- Invulnerability. A sense of immunity to error, failure, or injury. Most people do not believe they will err in the next few moments: “That can’t happen to me.” Error is always a surprise when it happens. This is an outcome of the human limitation to accurately estimate risk. The failure to secure enough lifeboats for all passengers and to train the seamen how to launch them and load them ultimately resulted in the biggest maritime loss of civilian lives in history on the Titanic. Invulnerability was so ingrained in the minds of the ship owners about the ship being unsinkable that to supply the vessel with life boats for all passengers was foolhardy and would somehow leave the impression that the ship could sink. Hence, only half enough life boats were brought on board for the maiden voyage. When disaster struck, seaman struggled to launch the available craft. In the panic and confusion, numerous boats floated away from the mother ship only partially loaded.

- Pollyanna – All is well. People tend to presume that all is normal and perfect in their immediate surroundings Humans seek order in their environment, not disorder. They tend to fill in gaps in perception and to see wholes instead of portions. Consequently, people unconsciously believe that everything will go as planned. This is particularly true when people perform routine activities, unconsciously thinking nothing will go wrong. This belief is characterized with quotes such as “What can go wrong?” or “It’s routine.” This attitude promotes an inaccurate perception of risk and can lead individuals to ignore unusual situations or hazards, potentially causing them to react either too late or not at all.

- Bald Tire. A belief that past performance is justification for not changing (improving) existing practices or conditions: “I’ve got 60,000 miles on this set of tires and haven’t had a flat yet.” A history of success can promote complacency and overconfidence. Evidence of this attitude is characterized with quotes such as, “We haven’t had any problems in the past,” or “We’ve always done it this way.” Managers can be tempted to ignore recommendations for improvement if results have been good. What happened with the Columbia space shuttle is a good example. Over the course of 22 years, on every flight, some foam covering the outer skin of the external fuel tank fell away during launch and struck the shuttle. Foam strikes were normalized to the point where they were simply viewed as a “maintenance” issue—a concern that did not threaten a mission’s success. In 2003, even after it became clear from the launch videos that foam had struck the Orbiter in a manner never before seen, Space Shuttle Program managers were not unduly alarmed. They could not imagine why anyone would want a photo of something that could be fixed after landing. Learned attitudes about foam strikes diminished management’s wariness of their danger.

At-risk behaviors are actions that involve shortcuts, violations of error-prevention expectations, or simple actions intended to improve efficient performance of a task, usually at some expense of safety. At-risk practices involve a move from safety toward danger. These acts have a higher probability, or potential, of a bad outcome. This does not mean such actions are “dangerous,” or that they should not ever be performed. However, the worker and management should be aware of at-risk practices that occur, under what circumstances, and on which systems. At-risk behavior usually involves taking the path of least effort and is rarely penalized with an event, a personal injury, or even correction from peers or a supervisor. Instead it is consistently reinforced with convenience, comfort, time savings, and, in rare cases, with fun..

Examples of at-risk behaviors on the job

- hurrying through an activity;

- following procedures cookbook-style (blind or unthinking compliance);

- removing several danger tags quickly without annotating removal on the clearance sheet when removed;

- reading an unrelated document while controlling an unstable system in manual;

- having one person perform actions at critical steps without peer checking or performing concurrent verification;

- not following a procedure as required when a task is perceived to be “routine”;

- attempting to lift too much weight to reduce the number of trips;

- trying to listen to someone on the telephone and someone else standing nearby (multitasking);

- signing off several steps of a procedure before performing the actions; or

- working in an adverse physical environment without adequate protection (such as working on energized equipment near standing water—progress would be slowed to cleanup the water or to get a rubber floor mat).

Risky behaviors at worksites have contributed to events, some causing injury and death, including:

- working on a hot electrical panel without wearing proper protective clothing;

- carrying heavy materials on an unstable surface while not using fall protection;

- failing to adhere to safety precautions when using a laser;

- operating a forklift in a reckless manner;

- opening a hazardous materials storage tank without knowing the contents; and

- failing to follow procedures for safeguarding sensitive technical information.

Persistent use of at-risk behaviors builds overconfidence and trust in personal skills and ability. This is a slippery slope, since people foolishly presume they will not err. Without correction, at-risk behaviors can become automatic (skill-based), such as rolling through stop signs at residential intersections. Over the long-term, people will begin to underestimate the risk of hazards and the possibility of error and will consider danger (or error) as more remote. People will become so used to the practice that, under the right circumstances, an event occurs. Managers and supervisors must provide specific feedback when at-risk behavior is observed.

Workers are more likely to avoid at-risk behavior if they know it is unacceptable. Without correction, uneasiness toward equipment manipulations or intolerance of error traps will wane.

Slips, Lapses, Mistakes, Errors and Violations

Error. People do not err intentionally. Error is a human action that unintentionally departs from an expected behavior. Error is behavior without malice or forethought; it is not a result. Human error is provoked by a mismatch between human limitations and environmental conditions at the job site, including inappropriate management and leadership practices and organizational weaknesses that set up the conditions for performance.

Slips occur when the physical action fails to achieve the immediate objective. Lapses involve a failure of one’s memory or recall. Slips and lapses can be classified by type of behavior when it occurs with respect to physical manipulation of facility equipment. The following categories describe how an incorrect or erroneous action can physically manifest itself or ways an action can go wrong:

- timing – too early, too late, omission;

- duration – too long, too short;

- sequence – reversal, repetition, intrusion;

- object – wrong action on correct object, correct action on wrong object;

- force – too little or too much force;

- direction – incorrect direction;

- speed – too fast or too slow; and

- distance – too far, too short.

Mistakes, by contrast, occur when a person uses an inadequate plan to achieve the intended outcome. Mistakes usually involve misinterpretations or lack of knowledge.

Active Errors

Active errors are observable, physical actions that change equipment, system, or facility state, resulting in immediate undesired consequences. The key characteristic that makes the error active is the immediate unfavorable result to facility equipment and/or personnel. Front-line workers commit most of the active errors because they touch equipment. Most errors are trivial in nature, resulting in little or no consequence, and may go unnoticed or are easily recovered from. However, grievous errors may result in loss of life, major personal injury, or severe consequences to the physical facility, such as equipment damage. Active errors spawn immediate, unwanted consequences.

Active errors are observable, physical actions that change equipment, system, or facility state, resulting in immediate undesired consequences. The key characteristic that makes the error active is the immediate unfavorable result to facility equipment and/or personnel. Front-line workers commit most of the active errors because they touch equipment. Most errors are trivial in nature, resulting in little or no consequence, and may go unnoticed or are easily recovered from. However, grievous errors may result in loss of life, major personal injury, or severe consequences to the physical facility, such as equipment damage. Active errors spawn immediate, unwanted consequences.

Latent Errors

Latent errors result in hidden organization-related weaknesses or equipment flaws that lie dormant. Such errors go unnoticed at the time they occur and have no immediate apparent outcome to the facility or to personnel. Latent conditions include actions, directives, and decisions that either create the preconditions for error or fail to prevent, catch, or mitigate the effects of error on the physical facility. Latent errors typically manifest themselves as degradations in defense mechanisms, such as weaknesses in processes, inefficiencies, and undesirable changes in values and practices. Latent conditions include design defects, manufacturing defects, maintenance failures, clumsy automation, defective tools, training shortcomings, and so on. Managers, supervisors, and technical staff, as well as front-line workers, are capable of creating latent conditions. Inaccuracies become embedded in paper-based directives, such as procedures, policies, drawings, and design bases documentation. Workers unknowingly alter the integrity of physical facility equipment, such as the installation of an incorrect gasket, mispositioning a valve, hanging a danger tag on the wrong component, or attaching an incorrect label.

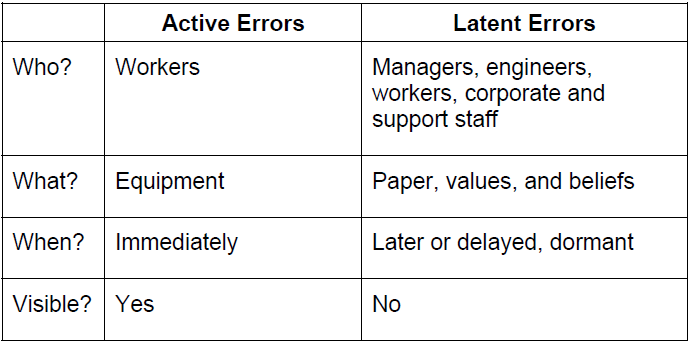

Usually, there is no immediate feedback that an error has been made. Engineers have performed key calculations incorrectly that slipped past subsequent reviews, invalidating the design basis for safety-related equipment. Craft personnel have undermined equipment performance by installing a sealing mechanism incorrectly, which is not discovered until the equipment is called upon to perform its function. The table below summarizes the general characteristics of each kind of error.

As one can see from the table, latent errors are more subtle and threatening than active errors, making the facility more vulnerable to events triggered by occasional active errors. A study, sponsored by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), focused on the human contribution to 35 events that occurred over a 6-year period in the nuclear power industry. Of the 270 errors identified in those events, 81 percent were latent, and 19 percent were active. The NRC study determined that design and design change errors and maintenance errors were the most significant contributors to latent conditions. The latent conditions or errors contributed most often to facility events and caused the greatest increases in risk.

Violations

Violations are characterized as the intentional (with forethought) circumvention of known rules or policy. A violation involves the deliberate deviation or departure from an expected behavior, policy, or procedure. Most violations are well intentioned, arising from a genuine desire to get a job done according to management’s wishes. Such actions may be either acts of omission (not doing something that should be done) or commission (doing something wrong). Usually adverse consequences are unintended—violations are rarely acts of sabotage. The deliberate decision to violate a rule is a motivational or cultural issue. The willingness to violate known rules is generally a function of the accepted practices and values of the immediate work group and its leadership, the individual’s character, or both. In some cases, the individual achieved the desired results wanted by the manager while knowingly violating expectations. Workers, supervisors, managers, engineers, and even executives can be guilty of violations.

Violations are usually adopted for convenience, expedience, or comfort. Events become more likely when someone disregards a safety rule or expectation. A couple of strong situations that tempt a person to do something other than what is expected involve conflicts between goals or the outcome of a previous mistake. The individual typically underestimates the risk, unconsciously assuming he or she will not err, especially in the next few moments. People are generally overconfident about their ability to maintain control.

Examples: When People Commit Violations

Research has found that the following circumstances, in order of influence, prompt a person to violate expectations.

- low potential for detection

- absence of authority in the immediate vicinity

- peer pressure by team or work group

- emulation of role models (according to the individual concerned)

- individual’s perception that he or she possesses the authority to change the standard

- standard is unimportant to management

- unawareness of potential consequences; perceived low risk

- competition with other individuals or work groups

- interferences or obstacles to achieving the work goal

- conflicting demands or goals forcing the individual to make a choice

- precedent: “We’ve always done it this way” (tacitly acceptable to authority)

The discussion on violations intends to help clarify the differences between the willful, intentional decision to deviate associated with violations and the unintended deviation from expected behavior associated with error. This course focuses on managing human error.

Dependency and Team Errors

For controls to be reliable, they must be independent; that is, the failure of one does not lead to the failure of another. If the strength of one barrier can be unfavorably influenced by another barrier or condition, they are said to be dependent. Dependency increases the likelihood of human error due to the person’s interaction or relationship with other seemingly independent defense mechanisms. For example, in the rail transportation industry, although a train engineer monitors railway signals during transit, automatic warning signals are built into the transportation system as a backup to the engineer. However, the engineer can become less vigilant by relying on an automatic warning signal to alert him/her to danger on the track ahead. What if the automatic signal fails as a result of improper maintenance intervals? Instead of one barrier left (an alert engineer), no barriers are left to detect a dangerous situation. There are three situations that can cause an unhealthy dependency, potentially defeating the integrity of overlapping controls:

- Equipment Dependencies – Lack of vigilance due to the assumption that hardware controls or physical safety devices will always work.

- Team Errors – Lack of vigilance created by the social (interpersonal) interaction between two or more people working together.

- Personal Dependencies – Unsafe attitudes and traps of human nature leading to complacency and overconfidence.

Equipment Dependencies

When individuals believe that equipment is reliable, they may reduce their level of vigilance or even suspend monitoring of the equipment during operation. Automation, such as level and pressure controls, has the potential to produce such a dependency. Boring tasks and highly repetitive monitoring of equipment over long periods can degrade vigilance or even tempt a person to violate inspection requirements, possibly leading to the falsification of logs or related records. Monitoring tasks completed by a computer can also lead to complacency. In some cases, the worker becomes a “common mode failure” for otherwise independent facility systems, making the same error or assumption about all redundant trains of equipment or components.

Diminishing people’s dependencies on equipment can be addressed by:

- applying forcing functions and interlocks;

- eliminating repetitive monitoring of equipment through design modifications;

- alerting personnel to the failure of warning systems;

- staggering work activities on redundant equipment at different times or assigning different persons to perform the same task;

- diversifying types of equipment or components, thereby forcing the use of different practices; for example, for turbine-driven and motor-driven pumps;

- training people on failure modes of automatic systems and how they are detected;

- informing people on equipment failure rates; and

- minimizing the complexity of procedures, tools, instrumentation, and controls.

Team Errors

Just because two or more people are performing a task does not ensure that it will be done correctly. Shortcomings in performance can be triggered by the social interaction between group members. In team situations, workers may not be fully attentive to the task or action because of the influence of coworkers. This condition may increase the likelihood of error in some situations. A team error is a breakdown of one or more members of a work group that allows other individual members of the same group to err—due to either a mistaken perception of another’s abilities or a lack of accountability within the individual’s group.

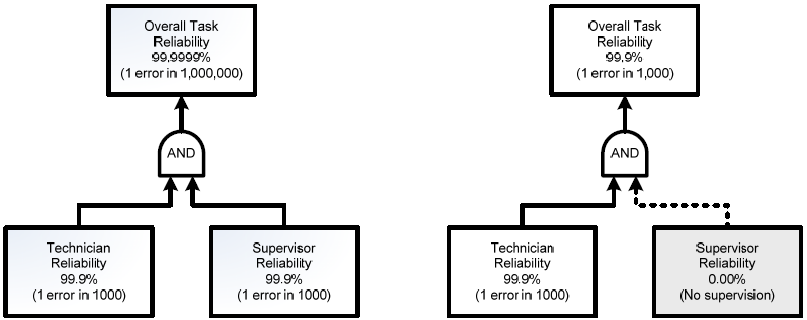

The logic diagram below illustrates the mathematical impact of such a dependency, using the example of a supervisor (or peer) checking the performance of a maintenance technician. Assuming complete independence between the technician and the supervisor, the overall likelihood for error is one in a million; the overall task reliability is 99.9999 percent. However, should the supervisor (or peer) assume the technician is competent for the task and does not closely check the technician’s work, the overall likelihood for error increases to one in a thousand, the same likelihood as that for the technician alone. Overall task reliability is now 99.9 percent. System reliability is only as good as the weakest link, especially when human beings become part of the system during work activities. The perception of another’s capabilities influenced the supervisor’s decision not to check the technician’s performance—a team error.

Several socially related factors influence the interpersonal dynamics among individuals on a team. Because individuals are usually not held personally responsible for a group’s performance, some individuals in a group may not actively participate. Some people refrain from becoming involved, believing that they can avoid answerability for their actions, or they “loaf” in group activities.36 Team errors are stimulated by, but are not limited to, one or more of the following social situations.

- Halo Effect – Blind trust in the competence of specific individuals because of their experience or education. Consequently, other personnel drop their guard against error by the competent individual, and vigilance to check the respected person’s actions weakens or ceases altogether. This dynamic is prevalent in hospital operating rooms, where members of the operating teams often fail to stay vigilant and check the procedures and actions in progress because a renowned surgeon is leading the team and there are several other sets of eyes on the task at hand. Each year it is estimated that there are between 44,000 and about 90,000 deaths attributable to medical errors in hospitals, alone. Never mind the transfusions of mismatched blood plasma, amputations of the wrong limbs, administration of the wrong anesthesia, or issuance of the wrong prescriptions. It is the medical instruments, sponges, towels, and the like left in patients’ bodies following surgery that are hard for laymen to understand.

- Pilot/Co-Pilot – Reluctance of a subordinate person (co-pilot) to challenge the opinions, decisions, or actions of a senior person (pilot) because of the person’s position in a group or an organization. Subordinates may express “excessive professional courtesy” when interacting with senior managers, unwittingly accepting something the boss says without critically thinking about it or challenging the person’s actions or conclusions.

Example of Pilot/Co-Pilot Error